Is my dog smiling? Interpreting the ‘happy’ dog – Dog Body Language

The complete article is available on www.silentconversations.com.

A human smile is easily recognized by an amused facial expression, denoted by up-turned corners of the mouth, at times with an open mouth and teeth exposed. Within the spectrum of differing human smiles there are nuances, with interpretations of each smile depending on subtle muscle changes around the mouth and eyes.

When it comes to observing a ‘smile’ in dog body language terms, it’s crucial to understand that this differs from the human understanding of a smile. Dogs ‘smile’ predominantly by the display shown with their bodies: how they are carried and how they move, along with observations of other body parts. The mouth plays a role in the overall dog body language observation, but on an auxiliary level, and it may be contrary to the human appearance of smiling. Signs that are commonly misinterpreted to suggest a dog is smiling include a wide open mouth and creases along the mouth commissure (corners of the mouth), with the commissure pulled back, with lips seeming extended and long, and panting with tongue protruding.

Dogs differ from humans when it comes to cooling themselves. They have a limited amount of sweat glands, which are located on their paws, and they cool themselves by panting. If a dog is panting, but not cooling himself or recovering from exercise, then the panting may indicate that the dog is experiencing some form of stress∗.

Understandably, smiling can be misinterpreted when applying what is familiar to us within our own species, to another species. Even with chimpanzees, a species whom we are close to biologically, we humans manage to misinterpret their facial expressions by incorrectly construing fear grimaces as smiles. Read about the difference between smiles and fear grimaces in chimpanzees here.

The wide open mouth panting, with tongue protruding, is misinterpreted as indicating a smiling dog. It is often used to justify an opinion that the dog feels happy, even when the observation of complete body language shows otherwise. It is questionable to presume a dog is feeling happy, even if the interpreted body language seems relaxed. We can approximate how the dog feels by interpreting the body language, but we can never know the exact internal emotions a sentient being feels from external observations. There are also nuances when it comes to smiling. For instance, a human can smile to appear friendly, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that, at the moment, the person feels happy internally. There is complexity when defining internal emotions from external visual cues. Although the dog may very well be happy, I prefer language such as ‘content’ or ‘relaxed’ when offering interpretations, as those terms are broader and don’t speculate.

What does relaxed body language look like?

A dog is lying on the grass in the garden. His body seems relaxed, as it is positioned slightly slouched to the side, with the dog having shifted weight onto one of the rear hips. The body is very slightly curved, with the front paws extended in front. No tension is noted in the body or muscles, and no furrows are seen on the dog’s face. His ears are to the side; occasionally they swivel to listen to the surrounding sounds in the garden. His eyes are almond shaped. The mouth is held slightly open, with a gentle pant, and the tongue is sticking out slightly but not extended. On occasion, the mouth closes gently when the dog focuses to listen to sounds. It is a warm summer’s day. His nose occasionally twitches, sniffing passing scents. The tail is lying passively on the ground and follows the curve of his body. This is an observation of a dog that typically seems relaxed; you could even interpret the dog is happy, but that is not necessary – relaxed suffices. The movement of the dog is slow and fluid, his body and muscles are soft, and there is no tension noted.

A dog is approaching a known person in a calm, relaxed manner: She sees the acquaintance in a park and picks up her pace slightly as she approaches the person. Her body is loose and moves easily by swaying loosely as she walks up. Her tail is the same height as the top line of her back, and it moves slowly in a wide sweeping motion from right to left. Her ears are slightly back, her eyes are almond shaped, and, as she nears the person, she squints slightly. Her mouth is gently open. She curves her body and walks in a very slight curving motion towards the person.

An example of an excitable body language response:

A dog is waiting near the door as his guardian returns home. As the door opens, the dog walks towards the person, with ears back and eyes slightly squinted. His body is moving fast and loose, making c-shaped curves, with the tail making wide motions very quickly and then intermittently wagging in a ‘helicopter’ circular pattern. The dog has a slight pant with open mouth. His body curves and moves in a squiggly manner, as he moves around the person quickly in circular patterns, displacing weight between his front paws and making small jumps up with his front paws. The dog also occasionally sneezes and intermittently lets out “huff” sounds as he moves around.

The fast movements indicate that the dog is excited. The sneezing can be interpreted as displacement behaviour, which also implies some excitement. The ears are back and eyes squinted; this could fall into the category of appeasement (the dog showing intention that he means no harm), which is typical in a greeting display. The looser moving and curving body show the dog is at ease. The panting is also due to excitement. You could say that the dog is ‘happy’, perhaps happy to see the person, but an objective interpretation would be that excitement is being shown. One detail from the observation that could be interpreted as ‘happiness’ is the ‘huff’ or ‘Huh, huh’, an exaggerated exhalation sound which is sort of equivalent to laughing in dogs. Patrica Simonet, a canine behaviour researcher, carried out studies where she recorded dogs’ ‘laughter’ during play¹. This breathy ‘huh’ or ‘huff’ sound, recorded on special microphones, showed it was made at a different frequency³ to other panting sounds and particularly made during play. These recordings were played to puppies and dogs in shelters. The dog-laughter played at the shelter seemed to reduce stress signals and encouraged the dogs to show pro-social behaviours².

The following is an example of a nervous /conflicted body language response:

A volunteer enters a shelter dog’s room to meet her for the first time. The dog moves forward towards the volunteer, with a curved body in a fast motion, the front of her body slightly lowered in a crouched down position. The tail is wagging with short, fast strokes, whilst the tail and tail base are held down below the level of the back top line. The dog’s ears are held fully back. Although her eyes are slightly almond shaped, they also seem to be quite open and bulging slightly, as parts of the white of the eye are visible (also known as whale eye). The dog’s head and front body dip down and away from the person. She intermittently lifts her head to look up to the volunteer; when she does so, her eyes squint, and she reveals her front teeth by lifting her lips. She lets out what sounds like a quick sneeze and does a tongue flip, turning her head and curving her body away. This sequence of movements continues, including a few more sneezes and quick successions of tongue flicks or lip licks.

The showing of teeth or grimace in this example is termed a ‘submissive grin’. Although this is the technical term used for the grin, I have not felt comfortable with the addition of ‘submissive’, as it implies an immediate interpretation which may not be accurate. I think calling it a grin, appeasement grin, or appeasement gesture, would offer a broader description without adding the subjective interpretation of ‘submissive’ to the term. Appeasement is a broader term that allows for various interpretations and reasons for the appeasement. However, ‘submissive grin’ is the technical term that is currently used.

Showing teeth in this context is an appeasement gesture and not an antagonistic gesture. It has nothing to do with an aggressive display, which would have different body language to go along with it, such as stillness, hard eye, and a few other body language postures. The interpretation of the totality of body language indicates this dog is feeling conflicted; she is showing a mixture of stress signals, appeasement, and calming signals. The fast, erratic movements show some excitement and are indicative signs of stress*. The fast, shorter movements of the tail, along with its lowered position, show some apprehension and tension. If the dog were feeling more comfortable, her tail would be at midline back height, moving in wider more fluid movements. The lowered body posture indicates signs of feeing unsure, and the dog is trying to show she means no harm. Her frequent lip licks could be interpreted as a stress response or calming signal, indicating some discomfort. The head turns are a calming signal, with her trying to showing she is not a threat. The dog is simultaneously approaching and moving away, with fast movements indicating nervousness and conflict. Fast movements fall into the ‘fidget’ category of stress responses, fidgeting is a physical response that indicates a stress response.

To see a further example of a ‘submissive grin’, visit Eileen’s (from eileenanddogs.com) breakdown of a video of a puppy showing a ‘submissive grin’.

The following are observations of dogs displaying body language indicative of stress:

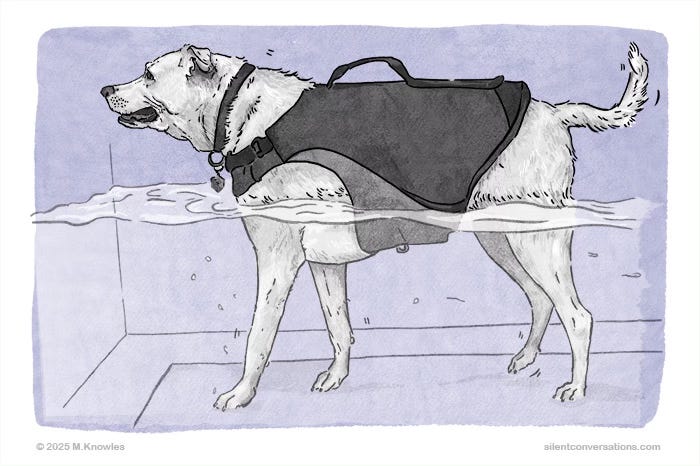

This is an observation of a dog undergoing physical therapy on a water treadmill. The dog walks at a slow pace on the treadmill, with water going up to her shoulders. She is accepting treats intermittently from her guardian, who is situated at the front of the machine. There is a second water treadmill, which is next to the one the dog is in. She is walking steadily with her ears back; her tail is held rigidly in line with her back, and the top of the tail is curled slightly up and held steadily in this position as she walks. Possibly, the tail is being used to steady her balance. Her mouth is closed at times and intermittently opens to pant, with the lips pulled back and extended, and deep creases along the corners (or commissures) of the mouth. Her eyes are wide and her head turns quickly in short movements to scan the room, while she takes treats from her guardian at intervals. She turns her head to look at another dog entering the treadmill next to her. Her mouth closes, her ears go forward, her eyes become wide, and she tilts her head when hearing the other dog’s guardian speak whilst coaxing his dog into the treadmill. Momentarily, she stops walking on the treadmill, and its belt carries her backwards. The therapist encourages her to walk again by calling her name, whereupon she turns her gaze back towards the guardian feeding her treats at the front of the machine. She takes a treat, and with ears back and eyes slightly squinted, continues to slowly walk on the treadmill. Then she opens her mouth again, and with wide lips pulled back and eyes wide, she pants again.

The wide mouth pant, along with the rest of the subtle body language observed, could be a sign of moderate stress for this particular dog. In this case, there might be a few reasons or a combination of reasons for her panting, which could be due to the physical exertion on the treadmill. However gentle, it might still be work for her, with her arthritis, to walk against the water. The environment is also quite busy, as other therapists walk around talking, and other dogs enter the therapy area. To focus on walking and trying to observe the environment could be quite taxing. This is also one of her first sessions walking on the treadmill when it is closed and filled with water, so she may be feeling slight unease. The other body language observed that shows unease includes the wide eyes, ears pulled back, tension in the facial muscles, along with furrows in the mouth corners, and the fast movements of the head scanning the environment. However, she does still feel comfortable enough to take treats.

Observation of a dog panting due to heat: A dog is lying in a sandy bit of the flowerbed, in full sun. The dog’s ears are pushed back, and the eyes are slightly squinted. The lips are pulled far back, with creases in the corners of the mouth or commissures. The tongue is hanging out and is extended over the bottom front canines. The extended tongue is wider at the base, and it almost resembles a spoon; this is known as a spatulated tongue. As well as the tongue looking spatulated, its end is held up as it lolls back and forward while the dog pants. The tongue being held up and not flopping over the teeth shows tension in its muscles. The dog’s chest and abdomen shake quickly as he pants. The dog is panting due to heat, and he is trying to cool himself. This could be classified as physiological stress. So, once again, this is not a smiling dog; this is a dog trying to cool himself while feeling hot.

A dog is pacing back and forth in a veterinary room as she waits with her guardian for the vet to enter the room. The dog’s eyes are wide, with pupils dilated. Her ears are held forward and occasionally swivel to the side to listen to the sound in the clinic. Her mouth is open wide, with lips long and pulled back, and furrows along the corners of the mouth as she pants. The tongue is quite extended, and the end of the tongue protrudes and is a wider ‘spoon’ shape at the base. This is a spatulated tongue and indicates tension in the tongue muscles. Her body is slightly lowered and her back is slightly roached, indicating body tension. The dog’s tail is held down, a sign of her unease. Her movements seem quite jittery as she paces, and she does not have many moments when she is not moving around.

Eileen and dogs provides an excellent photographic reference of how stress presents on facial expression.In a dog boarding facility, in an indoor socializing room, a dog is sitting in the corner, against the wall, as other dogs circle and walk around in the room. He is not interacting with any of the dogs in the room, but sits upright, with his ears forward, head held up. His eyes seem wide as he observes and keeps his eye on the activities of the room. There is tension in the muscles of his face, and he is panting, with a wide open mouth, tongue protruding, and deep furrows in the corner of his mouth. A dog approaches him to sniff around his face area. He remains seated and quite still; his ears are held back and he closes his mouth and turns his head away, averting the approaching dog’s gaze. The dog who approached moves away. Soon after the encounter, the dog that was sitting gets up. His movement is slow, and his body seems still, as he walks along the wall’s perimeter. His tail is positioned down and is held still. His ears move around, listening to the sounds in the room, and he stands still along the side of the wall and begins panting again.

With this being an indoor ventilated room, and the dog is inactive; the panting shows that the dog is feeling stressed in this environment. The furrows forming around his commissure, or sides of his mouth, indicate the tension in his facial muscles. The fact that he is choosing to not interact with any of the dogs, but staying on the periphery of the room, keeping still, and focusing on keeping his eye on all the activity, indicates that he is not relaxed or comfortable in this environment. Further indications of his discomfort are seen when he gets up and remains along the edges of the room, with tail down and a still body, while he continues to pant. In this example, the stillness in movement could show the dog is feeling stress and starting to shut down due to the environment he has been placed in without an option for escape.

In summary, all the body language needs to be considered in totality before an interpretation of observations can be offered. The mouth is one part of the observation and is not interpreted as smiling if it is wide open, panting. How the dog’s body moves along with the rest of the body language observed, dictates whether the dog is ‘happy’, or a more accurate description would be relaxed or contented. When the body is moving fluidly, with subtle curves of the spine, it show the dog is relaxed. Fluid body language movements indicate relaxed body language; this example could be the centre point on a spectrum of body language. On either side of that spectrum is the lack of movement or stillness or, alternatively jittery fast movement. The lack of movement, stillness, and tense muscles fall into stressed/fearful body language. On the opposite side of the spectrum, fast jittery movement would fall into being interpreted as stressed*/excited body language or can be grouped into the fidget category. To get the most comprehensive interpretation, all aspects of the body language have to be observed, along with the context in which they appear. The interpretation can be nuanced, dependent on combinations of body language. Observing body language can give a good approximation of the emotion the dog is displaying on the outside, but we will never be able to know all the complexity of what the dog may be feeling on the inside.

What is meant by stress∗?

When I mention stress, this does not necessarily imply negative emotion. I mean stress in the physiological sense. So certain body language signals can mean the dog is feeling some sort of emotional discourse. This discourse could range from positive to negative emotion. Both excitement and fear could have similar effects on the body, with various hormones being released and activating the sympathetic nervous system. The dog may be feeling uncomfortable/fearful or it could also be excited about something. When analyzing stress in body language, it is worth noting the frequency and intensity of the various body language signals.

A few notes to consider when observing dog body language:

Observation before interpretation

Interpretations should be offered only once you have observed the complete interaction and taken note of the wider picture. To offer an unbiased interpretation of the body language, observe and take note of the situation, taking into account the dog’s whole body, the body language signals, and environment first before offering an interpretation. List all the body language you see in the order that it occurs; try to be as descriptive as possible without adding any emotional language. For instance, saying a dog looks happy is not descriptive and would be seen as an interpretation rather than an observation.

You could, however, list what you observe: ears to the side, eyes almond shaped, slight shortening of the eye, mouth open, long lips, tongue out, body moving loosely, body facing side-on, tail wagging at a slow even pace at body level.

From the observation, I could interpret that the dog seems relaxed or comfortable. I still prefer to say relaxed rather than happy, as I feel you will truly never know exactly what the dog may be feeling on the inside emotionally. It is quite likely the dog may be feeling happy, but I prefer to comment on how the dog is behaving in response to the situation rather than presuming internal emotional states.

The importance of viewing body language within context

Interpretations can vary depending on the context. It is possible for certain body language to be used in different contexts and have subtle differences in meaning within those contexts. Individual body language signals should not be observed in isolation; the wider picture should be considered. Take note of what the dog’s body as a whole is saying. Keep in mind each dog is an individual with varying skills and experiences. What may be typical for one individual may not be for another. In order to observe body language in context, consider the following: the situation, body language signals, the body language expressed by all parts of the dog’s body, environment, and individuals involved. It is worth noting how the body language changes with feedback from the environment or the other individuals interacting.

1. Simonet, P.R., Murphy, M., & Lance, A. (2001). Laughing dog: vocalizations of domestic

dogs during play encounters. Paper presented at the Animal Behavior Society

Conference in Corvallis, OR.

2. Simonet, P.R., Versteeg, D., & Storie, D. (2005). Laughing dog: Reduction of stress

related behaviors in shelter dogs using recorded playback. Paper presented at the 7th

International Conference on Environmental Enrichment in New York, NY.

3. Volsche, S., Gunnip, H., Brown, C., Kiperash, M., Root-Gutteridge, H., & Horowitz, A. (2022). Dogs produce distinctive play pants: Confirming Simonet et al. (2001). International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 35, Article 58492

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375967641_Dogs_produce_distinctive_play_pants_Confirming_Simonet

Thanks and appreciation to Rosee Riggs for the prompt to write about this topic. Rosee is a Certified Separation Anxiety Pro Behavior Consultant (CSAP-BC) consulting online, and providing support to dog guardians with separation anxiety cases. To consult with Rosee visit her website good-dog-practice.com

© 2025 Silent Canine Conversations, LLC and Martha Knowles | All rights reserved, worldwide, for content on https://substack.com/@silentcanineconversations

The complete article is available on www.silentconversations.com.

What an interesting exploration of a dog "smile" and all the body language nuances we need to consider.

I was delighted to find that you are now on substack!